Original article by Peter J. Koehler, M.D., PhD1 published 16 April 2011 in World Neurology Vol 26 No. 2, Neurological History

Between 1870 and 1914, many American students and postgraduates visited European cities to complete their medical training. William Osler, the distinguished Canadian clinician and medical educator, stated that German universities became the second home of all who loved science, scholarship, and truth.

Indeed, thousands of American, Russian, and Japanese physicians went to Vienna – which the American pathologist William Welch called the "conventional Mecca of American practitioners" (American Doctors in German Universities, TN Bonner. Lincoln: Nebraska University Press, 1963, pp. 1-21) – and Berlin to pursue popular courses in neurology that were often held in English.

|

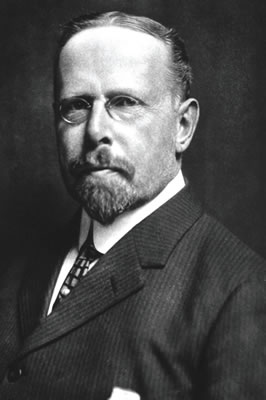

Bernard Sachs received his medical degree in Strasbourg during his European travels. |

After Vienna and Berlin, Paris and London were also important centres for those wishing to train in neurology. Among these students was the American neurologist Bernard Sachs (1858- 1944), who made a long European peregrination between 1878 and 1884. He studied under the German physicians Adolf Kussmaul, Friedrich von Recklinghausen, and Friedrich Goltz in Strasbourg, where he received his medical degree in 1882. He continued to Berlin, where he studied under Karl Westphal and where he likely also met Carl Wernicke; to Theodor Hermann Meynert in Vienna; Jean-Martin Charcot in Paris; and John Hughlings Jackson in London.

|

Theodor Meynert, "great as a scientific investigator; but as a teacher, far from great." |

In his autobiography, Sachs recounted his experiences during his postgraduate studies with Meynert: I began my postgraduate studies in Vienna in October of that year [1882] under Meynert. At that time, Vienna, with its famous Faculty and its far-famed Allgemeines Krankenhaus [general hospital], was the mecca of all American students. The hospital and teaching arrangements were such that one could easily get special courses and special laboratory opportunities in any subject. While cerebral anatomy and neuropsychiatry were my especial aims and took up most of my time …

But my chief purpose was to learn brain anatomy under Meynert – the great and most original brain anatomist. Great as a scientific investigator; but as a teacher, far from great. … Meynert and Westphal were great psychiatrists because they were also great neurologists. It would be fortunate if the young psychiatrists of the present day were trained in the same way, and not given certificates in psychiatry without the fundamental knowledge of organic neurology. …

In the laboratory, I found myself in good company. Allen Starr was a hard and patient worker. … Both of us were ambitious and were equally devoted to the advance of neurology and psychiatry in America [Sachs, B. Autobiography. New York, privately owned, 1949, p.56].

Here, Sachs met several other students, some of whom became famous.

Starr, [Gabriel] Anton, and I sat alongside of one another and close to Sigmund Freud, now by all odds the best known of the group. None of us suspected Freud's future fame. He pegged away at anatomy, as we all did, and although his doctrines took him far afield, in his last letter to me, written only a few months before his death, he acknowledged he had never severed his relations with organic neurology [Autobiography, pp. 56-7].

Indeed, Sachs was not very pleased with the psychoanalytic movement, especially with respect to dystonic afflictions. In reaction to an explanation of mental torticollis presented by L. Pierce Clarke in 1914, Sachs said, "if this indicated the future trend for our present-day neurology, then the less we heard of it, the better."

|

Jean-Martin Charcot, a "great French master of science." |

Sachs compared Meynert with Charcot and Hughlings Jackson, both of whom he visited after his stay in Vienna.

I spent a number of months with Jean-Martin Charcot at La Salpêtrière in 1883. It was a great experience, after the dry and matter-of-fact teaching methods of German scientists, to revel in the more or less dramatic presentation and discussion of clinical phenomena by this great French master of science. All Frenchmen, even to the lesser Professors, seem to be possessed by a dramatic fervour. Every lecture at La Salpêtrière or at the Hotel Dieu [sic] was as enjoyable as the average dramatic performance. I wish we British and American teachers of medicine had half the elegance of diction and half the skill in presentation of the average French instructor [Autobiography, p. 57].

In the spring of 1883, Sachs stayed with Hughlings Jackson in London and made a comparison between his Viennese and London teachers:

It became very evident, after a few days, that like Meynert, Jackson was not an easy man to follow. … I determined to get at Jackson's medical thinking, and … followed closely Jackson's publications, especially on epilepsy and aphasia… for many years, Jackson's views influenced me more than did those of any other teacher with the possible exception of Kussmaul [Autobiography, pp. 58-9].

Sachs returned to New York in 1884, where he entered general practice and devoted himself to neurology and psychiatry, starting the translation of Meynert's Psychiatrie. ■

Photos Courtesy Dr. Peter J. Koehler

Photos Courtesy Dr. Peter J. Koehler

Dr. Koehler is a neurologist, until 2016 responsible for the neurology training programme, in Zuyderland Medical Centre, Heerlen, The Netherlands with a special interest in neuro-oncology and headache. He is editor-in-chief of the Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, past-chair of the History Section of the American Academy of Neurology, History Section Editor of Cephalalgia and member of the editorial board of European Neurology, published books among others on Neurological Eponyms and on Brown-Séquard, as well as papers on the history of neurology, in particular on the history of headache/migraine.

Visit his Web site at www.neurohistory.nl